Kenneth W. Burchell

[an earlier version appeared in Free Inquiry, Vol. 29, No. 4 (June/July 2009)]

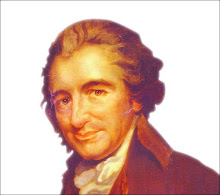

To understand what happened to the revolutionary experiment that began at Lexington and Concord with the 1775 "shot heard round the world"-- to understand how that revolutionary moment became 200 years later a banking morass of monumental size and an executive so strong that his powers are described as unitary -- there is no better model than Paine's life and his part in the political developments of the early republic. To understand what happened to Thomas Paine is to better understand the republic, past and present.

When Paine returned to the United States after a harrowing fourteen-year pilgrimage to France and England, he was the subject of a two-pronged welcome. On the one hand, he was lauded, celebrated, wined, dined, and escorted to the White House by President Thomas Jefferson's personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, of later Lewis and Clark fame. But all was not happiness and light.

His other reception was distinctly unfriendly. Well before his arrival, the Federalist press launched a campaign of slander, largely in response to Paine's Letter to George Washington (1796), a blistering critique of the person and policies of the former president and much-revered symbol of the Revolutionary War. When a rumor circulated that Jefferson had sent an American frigate to transport Paine back to America, Federalist partisans greeted the news with a historic campaign of published calumny:

"If, during the present season of national abasement, infatuation, folly, and vice, any portent could surprise, sober men would be utterly confounded by an article current in all our newspapers, that the loathesome Thomas Paine, a drunken atheist and the scavenger of faction, is invited to return in a national ship to America by the first magistrate of a free people. A measure so enormously preposterous we cannot yet believe has been adopted, and it would demand firmer nerves than those possessed by Mr. Jefferson to hazard such an insult to the moral sense of the nation." [The Port-Folio (Philadelphia), July 18, 1801]

"When the story arrived here, that the President of the United States had written a very affectionate letter to that living opprobrium of humanity, Tom Paine, the infamous scavenger of all the filth which could be raked from the dirty paths. . . ." [Gazette of the United States (Philadelphia) July 21, 1801]

"It is probably enough that the obscene old sinner [Thomas Paine] will be brought over to America once more, if his carcass is not too far gone for transportation." [Daily Advertiser (New York), July 22, 1801]

Two hundred years later, if we accept the argument that Paine's religious ideas caused this upheaval, we run the risk of falling for the same distraction perpetrated by the Federalists. Paine was never an atheist. He was, like Washington, John Adams, Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and many if not most of the Founders, a deist. Paine and his supporters recognized what some in our own time have forgotten, that Paine was attacked with the cudgel of religion on account of his political views. What were the views that made him so dangerous? What might they tell us about the ideological divisions that were present at the founding? And do they still persist? Fortunately, Paine left an unequivocal answer to the first question in eight Letters to the Citizens of the United States and Particularly to the Leaders of the Federal Faction (1802-1803). In honor of the bicentennial of Paine's death on June 8, 1809, therefore, let us first hear him in his own literary voice before asking in what ways the past lives in the present.

"When I sailed for Europe, in the spring of 1787, it was my intention to return to America the next year, and enjoy in retirement the esteem of my friends, and the repose I was entitled to. I had stood out the storm of one revolution, and had no wish to embark in another. But other scenes and other circumstances than those of contemplated ease were allotted to me.

"The French Revolution was beginning to germinate when I arrived in France. The principles of it were good, they were copied from America, and the men who conducted it were honest. But the fury of faction soon extinguished the one and sent the other to the scaffold. Of those who began that Revolution, I am almost the only survivor, and that through a thousand dangers. I owe this not to the prayers of priests, nor to the piety of hypocrites, but to the continued protection of Providence.

"But while I beheld with pleasure the dawn of liberty rising in Europe, I saw with regret the lustre of it fading in America. In less than two years from the time of my departure some distant symptoms painfully suggested the idea that the principles of the Revolution were expiring on the soil that produced them." [Letter I]

A new and counterrevolutionary spirit was, said Paine, afoot in America:

". . . a faction, acting in disguise, was rising in America; they had lost sight of first principles. They were beginning to contemplate government as a profitable monopoly, and the people as hereditary property. It is, therefore, no wonder that the 'Rights of Man' was attacked by that faction, and its author continually abused." [Letter I]

The key phrase is "profitable monopoly." Paine used the term as it was understood in his time to mean more broadly an exclusive set of privileges rather than the narrower corporate or marketing sense in which we understand the word today.

The list of the privileged began with Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists who led the movement for assumption of the states' Revolutionary War debts by the federal government and to fund the national debt through excise and other taxes. Both proposals were divisive. States like Virginia that had already paid most of their war debt were unhappy to be taxed in order to pay for less solvent states. Other anti-Federalists saw assumption and the excise tax as unconstitutional usurpations of states' rights and a dangerous centralization of power under the 1789 Constitution.

Hamilton's newly established Bank of the United States (BUS) was nearly as unpopular. A private company held in part by foreign investors, the first BUS was designed to manage the U.S. currency and to assist northern commercial interests and manufactures. Southern and western agricultural interests perceived little benefit and resented the imposition of the excise tax to simultaneously fund the private bank and federal expansion.

Hamilton and his conservative allies used the "whiskey tax" as an exercise in social engineering. When resentful citizens interrupted court proceedings and attacked tax collectors, Washington declared martial law and called out the militia under the command of Alexander Hamilton and Henry Lee to put down the "rebellion." No rebel units were ever found. In November 1794, hundreds of citizens were arrested, detained, and questioned under horrific conditions. In the end, scores were convicted and sentenced to monetary fines, while more than twenty men were imprisoned. Some of these were later released for lack of evidence, while others languished in prison until Washington issued a pardon eight months later in July 1795. One man died in jail, and two were convicted and sentenced to hang for treason but released under the pardon. It was the first time that the federal government used military force to suppress its own citizens.

A system of privileges and exclusive power is a monopoly.

"Fourteen years, and something more, have produced a change, at least among a part of the people, and I ask myself what it is? . . .

"The plan of the leaders of the faction was to overthrow the liberties of the New World, and place government on the corrupt system of the Old. They wanted to hold their power by a more lasting tenure than the choice of their constituents. It is impossible to account for their conduct and the measures they adopted on any other ground." [Letter II]

Paine had reason enough to believe it. Hamilton favored a U.S. Senate whose members served for life, and John Adams was quoted as favoring a hereditary monarchy. The 1789 Constitution created a mirror image of the British system of government: House of Commons=House of Parliament; Senate=House of Lords; President=King. Paine himself had earlier exposed the country's first large-scale military procurement scandal in the Silas Deane Affair. The 1794 Jay Treaty was seen as surrendering by knavery the rights and world respect won by arms and blood during the Revolution. And Paine nearly died under the guillotine in part through the adverse machinations of another crypto-monarchist, Gouverneur Morris, one of President Washington's closest allies and advisors. How far were the Federalists willing to go?

Paine identified a core anti-Federalist complaint in his second letter.

"When the plan of the Federal Government, formed by this convention, was proposed and submitted to the consideration of the several States, it was strongly objected to in each of them. But the objections were not on anti-Federal grounds, but on constitutional points. Many were shocked at the idea of placing what is called executive power in the hands of a single individual. To them it had too much the form and, appearance of a military government, or a despotic one.

"Others objected that the powers given to a President were too great, and that in the hands of an ambitious and designing man it might grow into tyranny as it did in England under Oliver Cromwell, and as it has, since done in France. A republic must not only be so in its principles, but in its forms." [Letter II]

Had the United States actually gotten an executive or a king simply called an executive? The John Adams administration outlawed criticism of the president with the Sedition Act of 1798 and made it a crime to

". . . write, print, utter, or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute."

The Alien Act portion of the new law extended the requirement for naturalization from five to fourteen years. In order to advance their agenda, Adams and the Federalists turned on America's former ally, raising a great hue and cry over the phony danger of an invasion by France.

"The late attempt of the Federal leaders in Congress (for they acted without the knowledge of their constituents) to plunge the country into war merits not only reproach but indignation. It was madness, conceived in ignorance and acted in wickedness. The head and the heart went partners in the crime." [Letter VI]

America had acted the part of a belligerent, an aggressor.

"Were America, instead of becoming an example to the Old World of good and moral government and civil manners, or, if they like it better, of gentlemanly conduct toward other nations, to set up the character of ruffian, that of word and blow, and the blow first, and thereby give the example of pulling down the little that civilization has gained upon barbarism, her independence, instead of being an honor and a blessing, would become a curse upon the world and upon herself." [Letter VI]

Remarkably and in the same letter, Paine called the advocates of preemptive war and the unitary executive the "Terrorists of America" and "Terrorists of the New World." They had used a phony war-cry to make criminals of their own people, consolidate a monopoly of power and privilege, and enrich their friends. How could this happen?

"That persons who are hunting after places, offices and contracts, should be advocates for war, taxes and extravagance, is not to be wondered at; but that so large a portion of the people who had nothing to depend upon but their industry, and no other public prospect but that of paying taxes, and bearing the burden, should be advocates for the same measures, is a thoughtlessness not easily accounted for." [Letter VII]

The country, during the time of the former Administration, was kept in continual agitation and alarm; and that no investigation might be made into its conduct, it intrenched itself within a magic circle of terror, and called it a SEDITION LAW.

"Violent and mysterious in its measures and arrogant in its manners, it affected to disdain information, and insulted the principles that raised it from obscurity." [Letter VI]

The administration of John Adams had, said Paine, legalized fraud, theft, and constitutional usurpation in the name of a phony war.

Thomas Paine's writings, particularly the Letters to the Citizens of the United States, speak powerfully to the core issues that still plague the American body politic: an unnecessary war utilized to consolidate power, privilege, and profit; no-bid contracts and other monopolistic practices; legislation and executive orders (fiat power) designed to curb constitutional rights in the name of security; the unitary executive and abuse of power; a private banking concern window-dressed as a quasi-governmental entity that doles out investment privileges to a select few; the panting enthusiasm of the war-whoop mentality ("If you're not with us, you're against us"); and the question of when if ever a democratic republic can justify preemptive military action. Many of the same forces operate now as in Paine's own time.

Paine died, of course, exactly two hundred years ago. And so we must once again consult the oracle of his writings to know if he was hopeful or despairing about the prospects for the American future.

"The Right will always become the popular, if it has the courage to show itself, and the shortest way is always a straight line." [Letter IV]

". . . reason is recovering her empire, and the fog of delusion is clearing away." [Letter VII]

"I know that it is the opinion of several members of both Houses of Congress, that an inquiry with respect to the conduct of the late Administration ought to be gone into. The convulsed state into which the country has been thrown will be best settled by a full and fair exposition of the conduct of that Administration, and the causes and object of that conduct. To be deceived, or to remain deceived, can be the interest of no man who seeks the public good; and it is the deceiver only, or one interested in the deception, that can wish to preclude inquiry." [Letter VI]

On the 200th anniversary of Thomas Paine's death, let us rededicate ourselves to perpetuating the democratic principles that he championed and execrate the autocratic forces that he opposed and still threaten the republic. Tom, long may you run. Long live the memory of your life, ideas, and works. Long live the products of your great labors.

______

Kenneth Burchell is a historian and editor of a new six-volume collection entitled "Thomas Paine and America, 1776-1809", London: Pickering and Chatto Publishers, 2009 (http://www.pickeringchatto.com/major_works/thomas_paine_and_america_1776_1809)

© Kenneth W. Burchell 2009, All Rights Reserved

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Thomas Paine and his followers, history of democratic reform, politics, commentary.

Followers

Pages

- Essays, Books and Lists

- Book Recommendations

- On the Bicentennial of the Death of Thomas Paine, June 8, 1809

- Thomas Paine and Bi-polar Disorder

- A Mystery of Two Portraits of Thomas Paine

- Review of Thomas Paine -- A Collection of Unknown ...

- Thomas Paine -- a descriptive bibliography.

- Birthday Party Politics: The Thomas Paine Birthday...

- Glenn Beck - No Thomas Paine - No Common Sense

- History of Democratic Reform: a bibliography